Published: 16 June 2023

Last updated: 5 March 2024

The former foreign minister argues it’s time for Australia to change its policy and join the 70% of UN members who have recognised Palestine.

Since a United Nations General Assembly Resolution vote in November 2012, Palestine has had the status of a state within the UN system. It is not a full member state but, like the Holy See, a non-member observer state. Australia – after a heady debate within the Gillard cabinet – abstained on that vote.

The State of Palestine has now been recognised as such by 138 of the UN’s 193 members, over 70% of the total. But Australia – along with the United States and most of its allies and partners – is not one of them.

Labor’s policy is now clearly that this should change. Initially passed in the form of a National Conference Resolution in 2018, then elevated to formal incorporation in the National Platform in 2021 on the motion of then shadow minister Penny Wong, the language is unequivocal:

The Party supports the recognition and right of Israel and Palestine to exist as two states within secure and recognised borders; calls on the next Labor Government to recognise Palestine as a state; and expects that this issue will be an important priority for the next Labor government.

But unequivocal platform language, as most of us who have been in this business are acutely aware, has never stopped Labor governments equivocating. That has been the case whenever they – we – have had cost-benefit doubts about the practical, principled or political wisdom of some party policy position. There has been no sign yet that the Albanese government is giving the issue any priority at all.

So the question for us now is whether any further equivocation on this issue is in fact justified, or whether it is time for Australia to grasp the moment and explicitly recognise Palestinian statehood.

I believe we should, but the case has to be argued, not just asserted. The counter arguments need to be met head-on. There are three dimensions to the debate – moral, legal and political – and I will look at each in turn.

The moral argument

The moral argument is the easiest to make: the righting of a grievous wrong done to Jewish people does not justify a grievous wrong being done to Palestinian people.

For what it’s worth, it was that perception – which first struck home to me when I read, as a university student in the 1960s, the classic Penguin Special Israel and the Arabs by the French historian Maxime Rodinson, both of whose parents were murdered in Auschwitz – which triggered my understanding of the Palestinian cause. It has been key to my support for it ever since.

Everyone understands the nature and force of the Jewish people’s claim to a recognised homeland with safe and secure borders, suffering as they did centuries of persecution, culminating in the horror of the Holocaust.

But it is equally impossible to ignore the moral force of the Palestinian response: that the world’s conscience should not be satisfied at the expense of a people who bear no responsibility for that suffering.

Palestinians deserved a state of their own. They were promised a state of their own by the UN General Assembly in 1947 in its resolution – which Australia’s H.V. Evatt played a crucial role in crafting – to partition the then-British Mandate of Palestine into two states: one Arab and one Jewish, with Jerusalem to be placed under a special international regime.

The design and implementation of the Partition Plan was only defensible if it involved, as its terms clearly did, no dispossession of Palestinians living in the new Jewish state, and no subsequent discrimination against them, and the same for Jews in the new Palestinian state.

But we now know all too well that the birth of Israel, and its whole subsequent history, was accompanied by no such restraint.

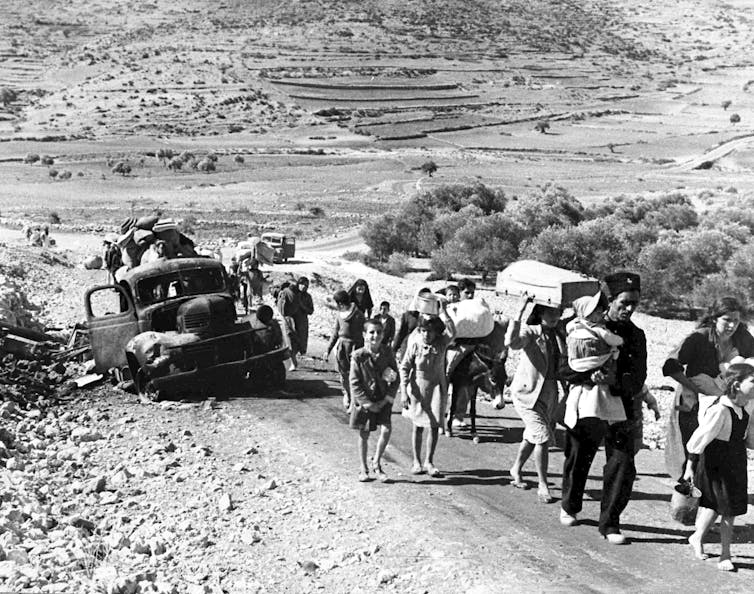

In the first Arab-Israeli War of 1948, triggered by Palestinian refusal to accept partition, the map was dramatically redrawn in Israel’s favour: 750,000 Palestinians became refugees.

In the Six-Day War of 1967, initiated by Israel as a "pre-emptive strike" against its Arab neighbours, East Jerusalem was illegally annexed. The remaining 22% of the former Palestine was militarily occupied, and the foundations were laid for what it is hard now to describe as anything other than an apartheid state – certainly so in the occupied West Bank, and only marginally less so now in Israel itself.

The Palestinian Declaration of Independence of November 1988, which referenced the original Partition Plan and subsequent UN resolutions, effectively recognised Israel and supported a two-state solution. But all subsequent attempts to implement such a solution, based on Israel withdrawing to its pre-1967 borders, have run into the sand.

Did Palestinians, and the Arab states supporting them, forfeit their moral claim to a state of their own by refusing for so long to accept the Partition Plan and initiating the violent resistance to the creation of Israel that ended so catastrophically in 1948?

That is an argument still heard from time to time – and it may seem to have some prima facie plausibility.

But if one is going to claim that, how could one not also accept that the moral claim to a new state of Israel was not tarnished by the violent extremism perpetrated by Irgun and the Stern Gang (or Lehi) in the pre-partition period, not least with the bombing of the King David Hotel in 1946 and the massacre at Deir Yassin in April 1948?

History teaches us it has forever been the unhappy reality that, in the pursuit of national self-determination, some of those most passionate for their causes have sometimes done things that have been misguided and counterproductive, and sometimes indefensibly terrible.

But the means chosen cannot in itself destroy the moral force, such as it is, of the end being fought for.

The legal argument

The UN Partition Resolution 181(II) of 1947 determined there was to be a Palestinian state alongside the Jewish one. Multiple resolutions since have reaffirmed the UN’s position. While general assembly – unlike security council – resolutions are not formally binding on member states, they are certainly persuasive: both politically and legally.

The boundaries of what that Palestinian state might be were effectively redrawn in 1948. They will necessarily require further renegotiation after the new facts on the ground created by the 1967 war and – illegal under international law as they may be – by Israel’s relentless subsequent program of settlement building in East Jerusalem and the West Bank.

But the UN has never resiled from declaring the necessity of a two-state solution, in which Palestine would have its own viable, recognised state.

Resolutions 242 (after the 1967 War) and 338 (after the 1973 Arab-Israeli War) – constantly reaffirmed since – make clear what the parameters of that solution should involve. They would include Israeli withdrawal from occupied territories and "a just settlement of the refugee problem".

But what is necessary in international law for a state to be recognised as such? And to what extent, if at all, is Australia constrained by that law in making its own recognition decision?

The issue is more complicated than it is sometimes claimed to be: there is in fact no single, universally accepted definition in international law as to what constitutes a state.

The definition in the 1933 Montevideo Convention on the Rights and Duties of States (ratified by 17 states in the Americas) is the familiar starting point. But it is by no means the finishing point.

Article 1 of the Montevideo Convention provides that

the state as a person of international law should possess the following qualifications: a) a permanent population; b) a defined territory; c) government; and d) capacity to enter into relations with other states.

Palestine does have, arguably, an identifiable population and its own government – albeit divided between the Palestinian Authority and Hamas, with neither in complete effective control of the territory they notionally govern. It does have theoretically defined territory – in the sense of the pre-1967 borders recognised by the UN – but those boundaries now are hardly recognisable in reality. They will be immensely difficult to recreate.

And while there remains far from universal acceptance by others of its sovereign equality, Palestine has demonstrated its capacity to enter into relations with other states.

It has done this by being accepted (as the State of Palestine, or the Palestine National Authority, or in some cases the PLO) as a full member of a number of international organisations: from the Arab League and Organisation of Islamic Cooperation to the International Telecommunication Union and World Health Organization. And it is accepted as an observer state in others, including the UN itself. It is also a state party to the Rome Statute, which constitutes the International Criminal Court.

Not everyone will be persuaded that all the Montevideo criteria are fully satisfied in the case of Palestine. This is obviously the case with organisations here like the Zionist Federation, which has made this a major objection, arguing that claims Palestine meets the minimum criteria for statehood is a "virtue-signalling" pretence.

But that is not the end of the story. The view that satisfying these criteria is both necessary and sufficient for a state to be regarded as such is just one school of thought in international law: the "declaratory" school. The other school – described as the "constitutive" school – takes the view that it is the act of recognition by others that leads to the creation of a state.

The argument here is partly that the Montevideo criteria cannot be regarded as the sole determinant of statehood: without the additional element of recognition, would-be states would lack international personality and would be unable to benefit from their international rights.

But the "constitutive" position goes further: it is recognition itself which really matters. And in the case of Palestine, while its recognition as a state by others is not yet universal, the fact that 138 UN member states (with Mexico reported as likely to be the 139th) now explicitly recognise its statehood is in itself a compelling legal – not just political – argument for others to do the same.

The political argument

If the moral arguments for Australian recognition are compelling, and the legal arguments against it anything but decisive, the argument – no surprise – comes down to politics: both international and domestic.

There are three international political arguments against our recognition that need to be countered: that recognition by anyone will destroy the peace process; that it is now useless; and that for Australia it would be damaging to our international reputation. Domestically, the argument is that it would be political folly for any party to go down this path.

The argument that recognition would destroy the peace process – undermining the capacity for a settlement to be negotiated, and completely premature to even contemplate until such a settlement is achieved – has been around forever.

If it ever had any objective credibility with anyone, it certainly has none at all now in the face of Israel’s breathtaking intransigence, being taken to ever more alarming new heights by the Netanyahu government. If the two-state solution is in fact dead, it is the Israeli settlement program that has killed it.

There will still be those who lay all the blame for the effective collapse of peace negotiations on a Palestinian regime that former Labor MP Michael Danby, with his usual flair for constructive diplomacy, described earlier this year as "homophobic, fundamentally undemocratic, kleptocratic, misogynist" and "scumbag".

No one doubts that the quality of Palestinian Authority leadership has been less than ideal, nor that Hamas’s formal (if not practical) position on Israel’s right to exist has been manifestly unhelpful.

But the evidence is clear – and my own years of direct talking with all parties, particularly as president of the International Crisis Group, strongly confirms it. The threat and reality of violence, whether by Hamas or anyone else, diminishes rapidly when Palestinians see a path ahead of genuine hope for a just and dignified settlement. And it escalates equally rapidly when they do not.

The argument that recognition is useless has gained more traction as hopes for a viable two-state solution continue to crumble – above all, as a result of the territorial fragmentation created by Israel’s indefensible West Bank settlement-building program.

What is the point, opponents say, of wasting time and energy – and, perhaps, political capital – on supporting a totally quixotic enterprise, never likely to bear fruit?

With all that acknowledged, it is important to keep the dream of a two-state solution alive. Not just because it remains overwhelmingly the preferred policy internationally, but because it is so obviously in Israel’s own long-term interest.

As many commentators over the years have pointed out, with compelling logic, Israel can be a Jewish state, a democratic state, and one occupying the whole of historical Judea and Samaria. But it cannot be all three.

The argument in this context for recognising Palestinian statehood is that it is crucially necessary to restore a balance that has in recent years tipped overwhelmingly in favour of Israel.

No peace negotiation has much prospect of succeeding if the parties at the table are completely mismatched. And the best – possibly the only – way to counter that for the foreseeable future will be for Palestine to show it has ever-increasing legitimacy internationally, not only in the Islamic world and global south, but among traditional pillars of the global north, like Australia and other allies and partners of the United States.

For Australia to climb off the fence on this issue would make a significant contribution to changing this dynamic. Giving Palestine some extra leverage and bargaining power is important and useful, whether or not the two-state solution proves to have any life left in it at all.

If it does, as we must all hope it does, this will be crucial in producing genuinely just and viable solutions to all the crucial outstanding issues, including boundaries, credible security guarantees for both sides, protection of the holy sites, and a formula that will credibly address the incredibly difficult issue of refugee rights.

If it does not – if the two-state solution is indeed permanently dead – and the only game left in town is the negotiation of a new, democratic, non-apartheid-cursed single state (into which the Palestinian population of the West Bank and Gaza is merged with fully equal rights to citizenship with Israel’s own Jewish population) then again anything that gives the Palestinians some more balanced power at the negotiating table is a consummation devoutly to be wished.

The argument that recognition would be reputationally damaging for Australia internationally has little to commend it. It is true it would place us outside our usual North America-Western Europe comfort zone (our fellow middle power and good international citizen role model Sweden excepted). But not in a way that could be expected to have any adverse impact on our diplomatic, defence, trade, investment or other national interests.

Supporting Palestinian statehood would put us in very good company with most of our global partners in the middle-power MIKTA group, comprising Mexico, Indonesia, Korea and Turkey, as well as ourselves. And more importantly, it will align us with not just Indonesia, but nearly all of our Southeast and South Asian neighbours, and key Pacific partners like Papua New Guinea.

If Australia’s future does indeed lie much more with our geography than our Anglospheric history – as I for one have long believed it does – recognition would be no bad call.

Domestic politics

Which leaves us, last but by no means least, with the domestic politics. None of us in any party – not least my own – is oblivious to the formidable lobbying power of the Israeli support organisations in this country, nor of their ability to characterise even the most cautiously expressed critiques of Israel as savouring of unconscionable anti-semitism.

But times are changing. Israel’s brand – long gradually diminishing, as its practices in the West Bank have been ever more credibly labelled as apartheid by internationally credible observers, from Jimmy Carter to Human Rights Watch – has been badly tarnished in recent times, here as elsewhere, by the extreme, overtly racist, right-wing extremism of the Netanyahu government.

There have been massive community demonstrations in Israel against some of its proposed measures – in particular to bring the judiciary to heel. But the democracy being campaigned for does not extend (some brave dissenting voices notwithstanding) to Palestinians living in Israel or under its control.

Within the Jewish community here, as in the US, new and more balanced voices are emerging – like the New Israel Fund. And the voices in Australian politics that have been most visibly arguing for recognition, such as former New South Wales premier and foreign minister Bob Carr, are hardly fringe dwellers outside the respectable mainstream.

Bob Hawke, an early very passionate friend of Israel, made abundantly clear as prime minister that it should accept the reality of Palestine’s aspirations to statehood. And, in his later years, he made equally clear his view that Australia should not hold back on recognition.

I myself have always supported Israel’s right to exist. And in fact as foreign minister, I resisted international efforts through the UN to characterise any support for Zionism as inherently and irretrievably racist. I have a plaque signed by Mark Leibler of the Zionist Federation of Australia to prove it!

What unites me and Hawke and Carr, and a legion of other Labor figures going back to Evatt, is not a belief that Israel should not exist, but that it should fully respect the rights of Palestinians to live alongside it in peace and dignity in a state of their own, and with the rights of dispossessed Palestinians appropriately acknowledged.

Maybe recognising Palestine statehood will put at risk some of our strongest traditional sources of party fundraising. But sometimes those considerations just have to take second place to decency. It is not a bad principle in politics – when in doubt – to do the right thing simply because it’s the right thing to do.

This article was delivered as an address to Parliamentary Friends of Palestine, Parliament House, Canberra, June 13 2023.![]()

Gareth Evans, Distinguished Honorary Professor, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Photo: Flagpole in Ramallah (Deborah Stone)